Highway Paleontology Program

A Mesozoic Plesiosaur

< Vertebrate Paleontology Home

The Highway Paleontology Program is a partnership between the University of Nebraska State Museum and Nebraska Department of Transportation.

December is not the ideal time to prospect for fossils in Nebraska. Regardless, Mike Baldwin, an amateur paleontologist and science educator from Brownsville Texas, braved the elements in search of shark teeth. As a kid growing up in the area, Mike was interested in geology and paleontology and frequently explored gravel pits, creek bottoms, roadcuts, and his family’s land for rocks and fossils. It was a relatively unsuccessful day looking for fossils between patches of snow and ice but his persistence paid off when he saw two large bones weathering out of the hill.

Mike collected the remains, marked the locality, and returned home. Due to their large size, he suspected they were plesiosaur vertebrae and contacted Mike Everhart, adjunct curator at Fort Hays (Kansas) State University, who confirmed this belief. The pair contacted Bruce Bailey, Highway Salvage Paleontologist at the State Museum, because the find was on state highway right-of-way. In the fall, the site near Center was revisited by Bailey, Shane Tucker (Highway Salvage preparator), Baldwin, and Everhart. At this time, ribs, pectoral girdle elements, paddle bones, vertebrae, and gastroliths (stomach stones used for ballast and/or digestion) were discovered in a small test excavation. The vertebrae were articulated (together as they would be during the animal’s life) and continued into the back wall of the pit suggesting more of the animal was buried beneath the hillside. The skeleton was more extensive than anticipated therefore the bones were reburied and the dig was postponed until Mike Baldwin could return in the spring.

Many questions were left unanswered for nearly six months. Which layer of rock contained the fossil? How old was it? How complete was the skeleton? Was it a long neck or short neck plesiosaur? Were the bones leading to the head or tail? If moving towards the head, would the skull be there? These unanswered questions led to much anticipation for the arrival of spring.

The skeleton was entombed in chalk, which consists of millions of microscopic phytoplankton skeletons that had fallen to the bottom of a shallow epicontinental sea. This seaway covered the interior of the continent during the Age of the Dinosaurs and stretched at times from the Arctic Ocean to the Gulf of Mexico. Dr. David Watkins, an expert on these microscopic organisms in the UNL Department of Geosciences, confirmed the layer of rock as the Mobridge Member of the Pierre Shale and estimated the age of the plesiosaur at 70 million years.

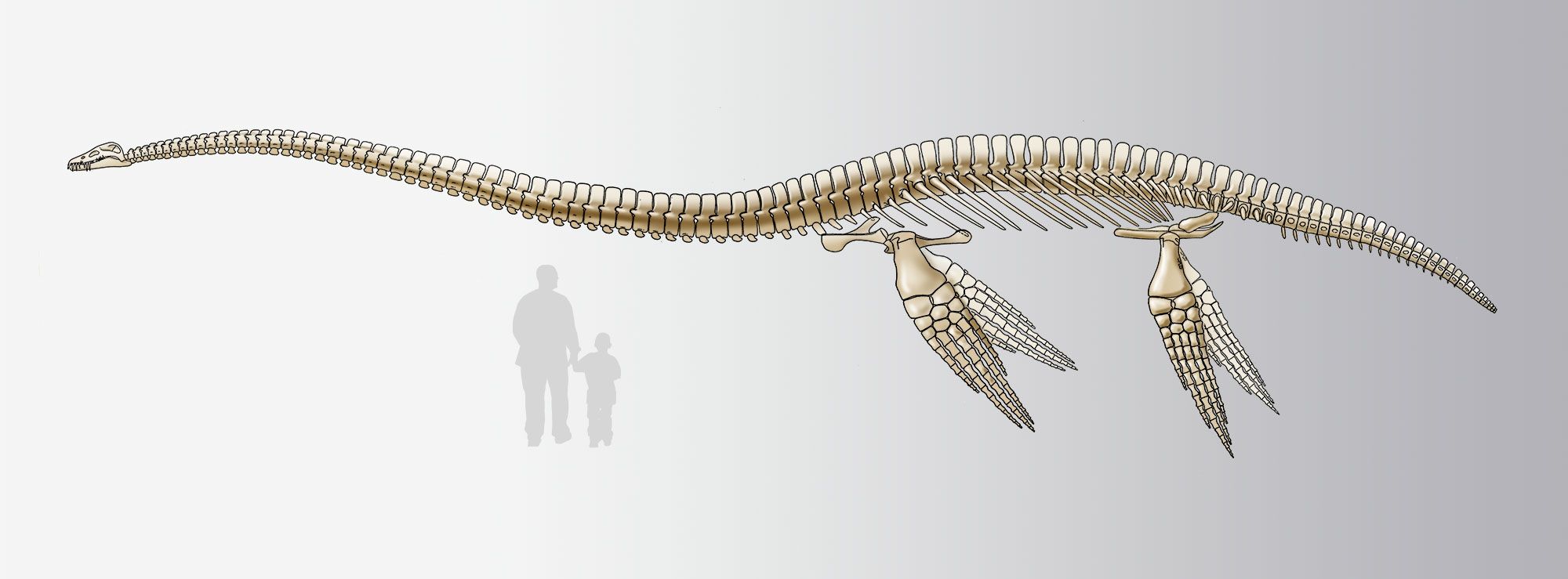

For two weeks in May, a crew of professional paleontologists and trained volunteers excavated, photographed, mapped, and plaster jacketed the remains. Shovels were used to remove overburden to within 8 inches of bone level and ice picks, scalpels, and brushes removed the remaining sediment from around the bones. The pectoral girdle, approximately thirty-five vertebrae, ribs, gastroliths, and many paddle bones were uncovered. Unfortunately, only one-third of the neck was present and the skull was missing. Long-neck plesiosaurs can have over 70 neck vertebrae. The remainder of the neck and skull may have fallen off before it sank to the bottom and was buried by the chalk. Commonly, sea animals float after death and begin to decompose on the surface where sharks and other scavengers can feed on the rotting carcass. During preparation, possible bite marks were found on the last few vertebrae supporting this scenario. The relative completeness and tight vertebral articulation suggest that the skeleton was not disturbed once it landed on the seafloor.

Articulated skeletons are rare in the fossil record as most skeletons are dissociated between death and burial. Since 1870, only five other partial plesiosaur skeletons have been found in Nebraska, all from layers of rock older than the Baldwin plesiosaur. The fact that this skeleton was even preserved is amazing in itself considering most skeletons are not buried quickly enough to prevent destruction.

Deposited near the end of the Cretaceous Period, the Mobridge Member contains some of the last marine reptiles. Mosasaurs and plesiosaurs were the largest predators in the sea. In addition to the plesiosaur, abundant remains of bony fish, clams, and ammonites were recovered during excavation, providing a glimpse into the seaway’s paleobiota.

The Baldwin plesiosaur now resides in Lincoln at the University of Nebraska State Museum. Regardless of its completeness, the specimen is scientifically significant and will be available for many generations to study. Many key elements for species identification are present in addition to more than 600 gastroliths that may provide insights into how these stones were used. Their lithologies will allow scientists to determine where these creatures swam to obtain their belly full of rocks.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the following people for their hard work throughout the excavation process: Travis Apel, Austin Baldwin, Connor Baldwin, Mike Baldwin, Roland Baldwin, Travis Baldwin, Ward Baldwin, Loren “Bub” Blake, Ray Branstiter, Greg Brown, Mike Everhart, Sam Matson, Angie Paquette, Michael Pedersen, Jerry Pekas, Brian Platt, Robert Randell, Keely Rennie, Lynn Sabotka, Mike and Jane Voorhies, Ben Vrana, Kristine Winter, and the Nebraska Department of Roads. Without a dedicated crew, a successful excavation like this would not be possible.

Contact

Any fossils discovered on highway right-of-way must be reported to Shane Tucker, 402-472-2657.