Special Collections

Luella Buros Collection

A collection of approximately 1,200 items of all sizes, materials, and manufacture, plus 12,000 slides in the African section alone, collected over four decades by Luella and Oscar Buros.

by Beth M. Willkins, Former Collections Manager

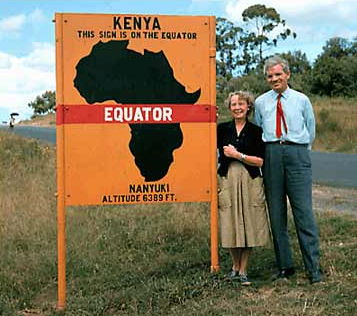

Luella and Oscar Buros at Equator sign near Nanzuki, Kenya. December 1961, elevation 6,389 feet

The Anthropology Division at the University of Nebraska State Museum contains a small, plain African ornament. It is not something that you would necessarily see on display, but its primary value as a research item is top-notch. It is part of the 1995 Luella Buros bequest, a collection of ethnographic material that, because of its size and detailed documentation, has generated a lengthy research project.

The entire collection is made up of approximately 1,200 items of all sizes, materials, and manufacture that were collected over the last four decades. It contains incredible masks and statues, costumes with elaborate embroidery, weapons, musical instruments, games, household goods and other items. Some items are extremely intricate and others are of simple construction. They are made of wood, copper, aluminum, silver, brass, ivory, bone, leather, and a variety of plant materials. They constitute a wide array of the material culture from an as yet undetermined number of countries. The collection comes from at least four continents, and many of the items purchased in the later years are from dealers of ethnographic material and foreign art, but much of the early African material was purchased "in the field". . . often right from the person wearing or using the items.

From the American Southwest and California are Navaho rugs and pots, fantastic Hopi Kachinas, and tiny coiled, horsehair baskets made by the Papago Indians; there is a Tarahumara drum and a Coyotepec figure from Mexico, Yanamamo baskets from Brazil, temple rubbings from Thailand, bells from Bali and Tibet, small bronze figures from Nepal, and gourds, necklaces, and baskets manufactured by the Huacayo and Ticuna people in Peru and Brazil.

Luella's notebook

drawing of an old Hopi

Kachina obtained from

the Nechta family.

The majority of the ethnographic collection is African, some 950 items and 12,000 slides. The acquisition doubled the number of African artifacts in the Division's ethnographic collections, and it is a major asset of the Museum. There are wood figures, dolls, ceramics, ivory carvings, snuffboxes, house posts, baskets, leather and gourd food containers, masks, textiles, costumes, weapons, cosmetic containers, and jewelry. The peoples represented include the Maasai, Turkana, Karamojong, Zulu, Swazi, Ndebele, San, Herero, Yoruba, Fulani, Ewe, Akan, Bedouin, Tuareg, and the list goes on. There is no lack of interesting material in the Buros collection, but experience leads us to believe that it is the small items that will have the most comprehensive records.

Which takes us back to the ornament. It is small, fitting easily into one's palm, made from a single piece of soft copper wire, multi-color glass beads, and sinew. The wire is bent double, and stretched along the length of the turn is a narrow strip of beading. The wire ends are left bare, and overall, the thing looks like a decorated bobby pin such as one would find in a Western drugstore. When examined closely you can see that the tiny beads are strung and woven into a mesh with sinew strands. Some of the strands are broken at a stress point at the bend, but because of the mesh structure, the beads are all still attached. There is also a tiny amount of greenish corrosion evident where the sinew and metal are reacting to each other, perhaps compromising the ornamentís structural integrity. Under magnification, it can be seen that not only is there corrosion, but the mesh is covered with a sticky, granular residue. Dirt (not unusual to find something like that in this collection)and the natural grease of the sinew is what makes it sticky. The physical condition of the ornament dictates special handling and storage considerations, information which is forwarded to the Collections Manager, and then noted in the computer record along with measurements, material with which the item is constructed, and the colors of the beads (red/white/yellow/blue) used. As yet, the catalog record does not show the ornament's origin and use or how it was acquired, but, because of the nature of the bequest, we know that the physical information we can record is not all that is available. The research scope widens to include the part of Luella Buros' bequest that makes the rest of it worthwhile . . . the records and slide collection that accompanied it.

With a collection of this magnitude, these records demonstrate why our research efforts concentrate on something like this tiny ornament, which by its outer appearance, would seem to be nothing special. But it is items like this, with fairly complete notes of origin and use, that are the most valuable for an Africanist interested in material culture. Just as field collections require good record-keeping to enhance their research value, it is the documentation that accompanies an ethnographic donation that determines its worth as an acquisition for the Museum. Why does it happen that the small items in the Buros collection are the best for research? Because, in this particular case, we know the Buros traveled mostly the bumpy, muddy roads of Africa either by car, Land Rover or Volkswagen van, which meant keeping their local finds small. Most important, however, is the knowledge that Luella Buros was a dedicated and detailed diarist, an artist, and a fine photographer. Therefore, the small items in the collection are more likely to be "field collected," and there may be a diary entry, a drawing or perhaps a slide, and a notebook record with information about the item.

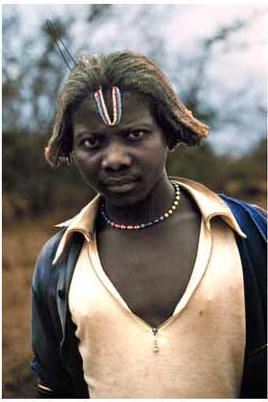

Forehead ornament purchased by Luella from this young boy in Swaziland, 1960. Photo by Luella Buros.

The ornament in question is one such find. Familiarity with Luella's journals and photo-logs reminds us that a handwritten entry exists about the purchase of a forehead ornament from a small boy along a South African roadway on or about August 14, 1960, in Swaziland between Pig's Peak (White River Mountains) and Nsoko. There is also an entry indicating there is a photograph. The entries are scrawled shakily in a small notebook, undoubtedly filled out in the car on some bumpy African road while her husband, Oscar, drove. Knowing Luella's penchant for accuracy, if we find this entry is related to the ornament we are examining, we will undoubtedly know exactly what it is, how it was worn and on whom, where it came from and the surrounding environment, and when it came into Luella's possession. This is where the value of the Buros collection lies, for not only did Mrs. Buros leave the Museum her extensive collection, she also left her travel records, which consist of numerous notebooks, extensive purchase records, drawings, multiple indices of the items, personal research notes, and over 300 books related to the countries she traveled in and collected from. In addition, there is a phenomenal 18,000 image slide collection documenting her travels. These written and visual records are of major interest to us because they provide contextual data vital to the research value of the collection. In the case of this head ornament, it has proven to be worth the effort to check to see if a picture exists of this particular ornament and the boy who wore it.

Woman with metal coils, Tangayika, 1961. Photo by Luella Buros

Another key element in documenting collections is to know who your donors are. One question often posed to museum professionals is, "Where do you get your collections? Who are your donors, and how do they find you or vice versa?" In the case of the Buros, I can briefly report the following facts.

Oscar Krisen Buros (1905-1978) was a statistician, a professor at Rutgers University in New Jersey. Born in Wisconsin, he attended, in turn, the Wisconsin State Normal School, the University of Minnesota, and Columbia University. He was affiliated with Rutgers from 1932 to his retirement in 1960 at the age of 60. He is best known for his Mental Measurements Yearbooks, which contained critical reviews of commercially available standardized tests in English-speaking countries. Mr. Buros firmly believed that the available tests (touted as miracle tools for helping teachers to predict a student's ability to achieve) were over-rated. To this end, he solicited test reviews from professionals in education, psychology, and testing for publication. Founded in 1938, there were eight yearbooks published before his death in 1978. Over the years, money came in from different sources ranging from WPA funds to small grants to Rutgers University financing. Eventually, the Buros created Gryphon Press and from 1940 onward, Oscar and Luella became partners in the organization and publication of the yearbooks out of their home. His professional standing brought may honors and awards, two of which led him to Africa: a senior Fulbright lectureship in statistics at Makerere University College, Uganda (1956-57) and an appointment as an advisor on educational testing in several African countries under the Ford Foundation (1965-67). These honors and the yearbook series are important links that tie the Buros collection to the Museum.

Luella Gubrud Buros (1901-1995) was born in Minnesota and spent her youth in North Dakota. She attended Columbia University, Rutgers University, and the Ohio State University. In 1920 she moved to Superior, Wisconsin to take a job that her sister Mabel had secured for her. This was where she met Oscar and, in 1925, they were married. Luella played a vital role at Gryphon Press, putting aside her own vocation as a talented artist to help publish the yearbook series. Beginning with wild rides Oscar provided on Wisconsin National Guard Cavalry Division horses during their budding friendship, the couple went on to spend thirty years riding camels, elephants, and ostriches in such places as India, Mongolia, and South Africa. Luella recorded it all in dozens of notebooks, inventory logs, diaries, and with thousands of slides. The Buros also purchased hundreds of items on their treks, many of which now reside in the Museum along with the slides, records, and hundreds of Luella's illustrations. Luella's visual acumen shines through in her drawings and in the meticulous compositional and technical care she brought to her photography.

When Oscar Buros died in 1978, Luella wanted to make sure that there would be a place for his work to continue. She found it at the University of Nebraska, and, with the aid of the University of Nebraska Foundation, the Buros Institute of Mental Measurements opened its doors at Bancroft Hall in 1979. It was this association that led to her meeting with Dr. Thomas Myers, Curator of the Anthropology Division. At the request of the Foundation, Dr. Myers made several trips to Luella's Arizona home to photograph and evaluate the items she had brought back from the Africa years as well as those purchased after her trips abroad. These visits were productive, and, in 1988, the Museum received Luella's first donation, two costumes from Ghana and Cameroon. The Ghanian "hunters" tunic and helmet are currently on display in the African Exhibit at Morrill Hall. Luella continued to send more items to the Museum. Over fifty textiles in the forms of yardage and costumes with masks were donated in 1990, and the Museum received over 225 items in 1992. She continued to correspond over the years, and when she died in 1995, she left the bulk of her remaining collection and her research library to the Museum. The slide collection was not included in the bequest. After being assured that the slides were of interest to the Museum because they would compliment the collections, and that they would be properly housed, Luella's niece, Arlene Haugen, decided to donate them. Besides the superior quality of the photography, the candid images Luella recorded in many countries during their transition from colonial rule to independent government cannot be underrated. The images provide an incredible visual history of cultural customs. There are also records of changing environmental conditions and wildlife habitat. With over 18,000 images from thirty years of world travel to be studied, their value as historical visual documentation of a metamorphosing world is just now being realized.

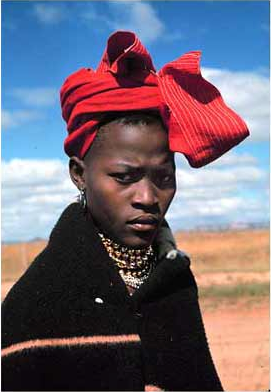

Basuto woman in Natal Province, South Africa, with fancy head wrap, 1962. Photo by Luella Buros.

The slides were shared by Luella over the course of years through slide shows that she would organize under the following headings: men, women, children, architecture, art, women's activities, men's activities, scenic, transportation, animals, etc. They include trips to game parks, animal orphanages, schools, government functions (including a Nixon visit), and records of their "safaris". In some cases, where she made more formal "portraits," Luella would record the name and address of the subject in order to send them a printed copy at a later date. Oscar also took pictures, but in his case it was mostly Polaroid prints. He would frame them in cardboard and give them to the people he photographed, much to their amazement and pleasure.

The range of Luella's interest was broad, but the meticulous order in which she kept her notes and the slides themselves makes it possible to catalog the collection. It is only in Buros' notebooks, diaries, personal recollections, and photographs that one will find the heart of the collection. The documentation was not recorded by a professional ethnographer trained in interview techniques. Instead it was chronicled by a woman who was blessed with a talent for observation, a boundless curiosity about people and their surroundings, and a camera. Eventually, the Anthropology Division hopes to be able to share the images with the public, researchers, and cultural heritage institutions in the countries the Buros visited.